By Gretchen M. Reevy, PhD (Lecturer, Psychology Department, California State University, East Bay)

When we think of people who live below the poverty line in the U.S., we often picture individuals who lack adequate medical care, who are homeless, who are unable to provide nutritious food for themselves and their families, and if young, people who are unable to prepare for their old age. Would you put college teachers in this category? A fact that may surprise you is that many college teachers earn very low incomes and some are even among the poverty-stricken in the United States.

These individuals possess Master’s degrees and PhD’s and are doing professional work. I am referring to non-tenure-track (NTT) faculty. These include adjunct professors, lecturers, post-docs, and others. The impoverishment of NTT faculty is an unknown and unexplored issue.

In the United States today, 76% of faculty in higher education are hired off the tenure track (AAUP, 2014). However, if you are an NTT faculty member, that nearly always means you are hired on a contingent basis. This means that each class you were hired for may be cancelled at the very last minute, due to insufficient enrollment, budgetary issues with the university, or other reasons.

According to Adjunct Action (2014), adjunct professors in the United States make $3,000 per 3-unit course, on average. Let’s say that as an adjunct faculty member you teach four courses per semester for two semesters. You supplement this income by teaching three additional courses during summer session. This translates to $33,000 per year.

In order to survive, NTT faculty take on workloads that make it nearly impossible for them to develop their careers. It is difficult to spend less than 10 hours per week teaching a class (including face time, preparation, grading, emails with students, etc.). An NTT faculty member may spend 15 or more hours per class per week if they are an experienced instructor (and even more if they are inexperienced). Therefore, I estimate that teaching four courses means working 40 to 60 or more hours per week for NTT faculty. This leaves little or no time to supplement what is, for most, an already inadequate income.

The shaky financial situation NTT faculty face is even worse when you take into account that they are typically saddled with student loan debt, often from both their undergraduate and graduate educations. NTT positions also rarely include the possibility for promotion or for enhanced job security over time. While adjunct positions are often the only professional work available to many qualified candidates emerging from graduate school, many can tell you that experience as an adjunct effectively labels you as “sub-par” and severely reduces your odds of obtaining a full time or tenure-track position.

The NTT faculty member making $33,000 per year would actually be among the relatively lucky. Many NTT faculty teach only one to two classes a semester because their institution limits the number of classes that part-time faculty may teach. They have to work their way up to a full-time load, which can take over two years or more. I just heard from an adjunct who has been teaching four courses a semester at $2,000 per course, and he is rarely allowed to teach in summer. He makes $16,000 a year.

The NTT faculty problem is too large for us to ignore. In the United States there are now at least 1.4 million NTT faculty (Curtis, 2014). It is certainly not the case that all of these faculty are impoverished or nearly impoverished; some are fortunate enough to work for universities that pay them relatively well and some have spouses or partners who make more money than NTT faculty do. However, the number of people affected by the impoverishment of NTT faculty also extends to their families (many NTT faculty are single parents).

If we work to help these faculty, we will aid a large number of Americans and we will be “doing the right thing.” My position is that most of the NTT faculty positions should not exist in their current form. Many aspects of the positions are simply immoral (in my view), in particular:

- the exceptionally low pay,

- lack of access to health insurance,

- contingent nature of the employment, and

- lack of opportunity for advancement.

The administrations of many universities argue that they can no longer afford to hire most faculty into secure positions and pay professional salaries. However, the AAUP (2014) counters that the decline in secure positions and salaries for NTT faculty is not economically necessary. In the last few decades universities have prioritized investing in facilities, technology, and other segments of the university over investing in faculty.

What can we do to help NTT faculty?

- Educate ourselves about NTT faculty and their working conditions. The best places to start are the New Faculty Majority, the American Association of University Professors, and the Coalition on the Academic Workforce, which has produced an excellent report on working conditions of part-time faculty.

- Researchers can study psychological effects of the working conditions of NTT faculty. My colleague, Grace Deason and I recently published an article on correlates of contingency. We found that several demographic and psychological factors were associated with elevated rates of depression, stress, and anxiety. Appropriate to the current discussion, one of these factors is low family income. Another is the NTT faculty member’s emotional commitment to his or her university. The more committed faculty suffer higher rates of depression, stress, and anxiety. Grace and I found that, at the time of publication of our article, no one else had studied the psychological effects of contingent appointments on faculty (to our knowledge).

- Encourage our professional organizations to join the Coalition on the Academic Workforce (CAW). The CAW is a group of disciplinary associations and faculty associations whose mission is to improve faculty working conditions (particularly for part-time faculty) and thereby improve higher education for our students. The leading professional associations for many academic professions are members (e.g., history, philosophy, modern languages); many other professional associations are glaringly absent from the list of members.

- Speak out publicly and put pressure on universities to alter their practices.

To conclude, I ask you—

- What does it tell us about our society that many of the faculty educating our future professionals are themselves barred, perhaps for the duration of their careers, from the security provided by a normal academic salary?

- And what does it say about the future of research when so many adjuncts receive neither the resources nor the time to do research, instead teaching full time just to survive?

NTT faculty make enormous contributions to our society. They deserve reasonable working conditions and pay that is commensurate with their education, experience, and other qualifications.

References

Adjunct Action. (2014). The high cost of adjunct living: St. Louis. Available online at: http://adjunctaction.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/18851-White-paper-st-louis-FINAL_E.pdf (Retrieved September 2, 2014).

American Association of University Professors (AAUP). (2014). Background Facts on Contingent Faculty. Available online at: http://www.aaup.org/issues/contingency/background-facts (Retrieved September 3, 2014).

Curtis, J. (2014). The Employment Status of Instructional Staff Members in Higher Education, Fall 2011. Washington, DC: American Association of University Professors.

Acknowledgments:

Thank you to Kent Goshorn, who provided extensive feedback on this essay.

Biography:

Gretchen M. Reevy received her BA in Psychology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and her PhD in Psychology from the University of California, Berkeley. Since 1994 she has taught in the Department of Psychology at California State University, East Bay (CSUEB) as a lecturer, specializing in personality, stress and coping, psychological assessment, and history of psychology courses. With Alan Monat and Richard S. Lazarus, she co-edited the Praeger Handbook on Stress and Coping (Praeger, 2007). She is also author of the Encyclopedia of Emotion (ABC-CLIO, 2010), with co-authors (and CSUEB alumnae) Yvette Malamud Ozer and Yuri Ito. With Erica Frydenberg, she co-edited Personality, Stress, and Coping: Implications for Education (IAP, 2011). Her research areas are in personality, stress and coping, psychological experiences of contingent faculty, emotion, college achievement, and the human-animal bond. Dr. Reevy publishes with CSUEB students, CSUEB alumni, and faculty colleagues in these research areas.

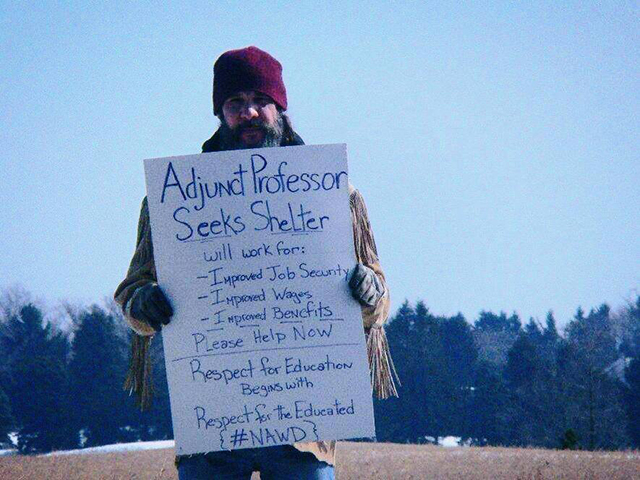

Image credit:

The above image is of a protester during National Adjunct Walkout Day on February 25, 2015. Permission to use the photo has been secured from the individual pictured.

This is my story. I work as an Adjunct and Dissertation Mentor. I have a PhD in Psychology, an MA in Clinical. Last year I took home 20K, no benefits, no health insurance, no retirement. This is my last week teaching a doctoral level research course–8 weeks. I had 13 PhD students, and the entire course paid $2,500 before taxes. I am paid as an independent contractor.

I am now training (no compensation) to teach as Adjunct at a second university. I was hired and trained to begin the Fall semester in October, and now they cannot tell me “for sure” what classes, how many classes, or what my contract will be.

I have two teenage children and my husband recently left after 18 years of marriage. Now, I am faced with the hard choice to leave professorial work altogether and return to teaching high school. But before I can do so, I have to get a credential.

How is this right?

LikeLike

Why are you doing this? Do you enjoy being part of the problem and not part of the solution? What you have to say is not news…the packaging is new, but so what? The only way for things to get better is if, beginning with highly trained individuals like you, we all begin to quit in droves and discourage others from following our particular path. The oppression will only end when the full timers, administrators and other fops and fools have nobody in their sodden cesspool (labor pool) to fish out and consume.

Eat the porcariat, quit the menial work and move on…The system is not just broken…it is profoundly broken…and the only way to make it better is to turn it upside down and dismantle it. I have worked within the system for over 20 years, been an advocate and a leg. analyst for nearly that long, and while I am satisfied with my role to date, I do not see the solution coming anytime soon.

So, I say, EAT THE PORCARIAT, (my term for the pork that is full time tenured faculty and administrators).

Save yourself and your self-esteem…just bite the bullet and move on, while encouraging others to do so. No more training, no more “professional development,” no more pandering and no more sub-standard pay…EVER..

How much longer, Precariats?

RBYoshioka

CPFA

LikeLike

No, I don’t think the solution is for adjuncts to quit work, that they love. The solution is to unionize. We at Montgomery College in MD have seen our pay increase 26% in the last four years. We now get one paid day off per semester, as well as time for jury duty and bereavement leave. We get $600 of professional development funds to go to conferences. We have a procedure for filing grievances when administrators and department chairs break the employment contract we bargained. If your state does not allow collective bargaining, then you need to organize your fellow adjuncts and go to the statehouse.

LikeLike

I’d love to make $3000 for a 3-unit course! I’m lucky to make $400 per credit hour each semester before taxes. But then, that’s Kansas for you. They don’t seem to understand that if they could give me a consistent class-load so I don’t freak every 15 weeks as the days tick by and I worry about paying bills the next semester with fewer classes, and if they could pay me $750 a credit hour, I’d be much happier.

How is it that tuition for an AA/AS around here is $20k, I have 10-20 students per class, and they can’t find enough to pay me a living wage? Colleges have forgotten that the purpose of college is to go to class and learn….from a teacher- so they kind of need faculty.

Why do I have embarrassment of bar tending at night, where I see my students come in and I serve them expensive drinks, simply because the tips from a weekend at that second job are more than my weekly pay teaching 10 credit hours?

Luckily, it’s Fall so between two colleges I have 21 credit hours to teach. Maybe I can pay off all of the debt that comes around each summer as I try to pay bills and squeak by.

LikeLike

This is not right and it is an extremely sad reality. My heart goes out to many of you because I know how difficult it can be to survive, with children and divorced, on a full-time faculty salary. What can we do? How do we have solidarity with our PhD brothers and sisters and where do we hold systems accountable? This is another form of cheap and exploitative labor.

LikeLike

A nation wide strike might be a good place to start.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Been there, done that…this suggestion is like telling us to effectively herd cats…not gonna work. The full-time dominated unions are NOT our friends…they are exploiters of our labor…never mind what they SAY. Just look at how takes home how much money. Go to: TransparentCalifornia.com and click on any community college district and then ask the software to list salaries of both full time and part time teachers. If that doesn’t make you want to quit immediately, then I don’t know what will.

There is no fairness…no justice…no “equal pay for equal work.” What exists is a system that is designed to keep the fat getting fatter, the skinny near death and indebted, and the whole system running on our slave labor.

We do not even make as much as casual day laborers or restaurant staff.

Wake up.

How Much Longer, Part Timers?

RBYoshioka, Ph.D.

CPFA

robertby07@gmail.com

LikeLike

Robert, I agree with you that we should discourage any of our students from pursuing academia as a career. But some of us are in no position to quit our jobs. Some of us, besides being parents, are older and have little hope of making a better living doing something else. That is my situation. So instead of giving up, I have joined my union board and am fighting like hell to make things better, Anyone who is a union member, please go to your state conventions and advocate for your union to start fighting for part-timers. Most unions have funds to send delegates to conventions, so you can get your trip and hotel room paid for if the convention is out of town for you. PLEASE go and speak your mind!

I don’t think we should give up and leave. I think more of us have to commit to fighting for change.

LikeLike

We do not even make as much as casual day laborers or restaurant staff.

At the risk of sounding cruel, didn’t you know the deal when you went into this profession? Did you not make the choice to pursue a career in academics? Are there not other means and avenues of employment open to you where you could make more moneY? Are you an indentured servant? That’s what’s great about this country, you aren’t in a caste system…you have choices. If teaching at the university level is your passion, as long as you know the deal when you get in, then deal with it.

LikeLike

Sure, what you say is logical. But step back, Mr. Parker, and think. Why should any work as valuable as imparting knowledge to our young people… to our future as a country…. be paid so little? That is a scandal!

LikeLike

Thank you for writing this. These insights need to be repeated again and again as the vampires within the system actively recruit unsuspecting victims, without ever really revealing the truth before it is too late e.g. they are deeply in debt, other avenues are closed to them, etc. Yes, in fact, yell it from the rooftops so the brainwashed students, some of them being actively recruited during their 4th year, can unlearn the damaging messages they have been given by given by their unscrupulous professors who want to maintain a steady supply of slave labor. Except for the select few, most of their lives will be ruined. Unlike their tenured well-paid compatriots, they will be abandoned and forgotten and left to die on the streets alone. There is no love for the adjunct in the end, no one cares what happens to them.

Like Charlie Gordon, they are led to believe (many of whom are poorer and do not understand the system very well) that they will be given in a new life, when in fact, what they are being prepared for is a life of servitude and hardship, hoping that “Masa” will eventually give them their freedom so they can exploit others. Lots of administrators will argue that it is well-known fact that a Phd no longer lead to a job in academia, when in fact, it is the rare administrators who openly acknowledge this “fact.” Despite their protests otherwise, these people operate largely in secret, hypnotising the young and grooming for a life a servitude with dubious promises of future reward. Keep posting, keeping telling the truth, until the vampires at the top will finally have no more blood to suck. It is one of the most abusive systems out there, totally mind control over unsuspecting, idealistic people who are hood-winked and lied to all the way, by so-called “eminent” scholars. Eminent my ass. I am surprised that while Bernie Sanders looked at the atrocity of high student debt, he did not delve into the slavery at academia–yet another indication that this problem is a well-kept secret, and needs to be constantly brought out into the open.

LikeLike

I have been an adjunct now for 14 years. Though I have made it to the second round of interviews for full time positions on several occasions to no avail. I “supplement” my income with homelessness. Not paying rent in San Diego is like having a fourth job. By not paying rent, as an adjunct instructor for going on 10 of the last 14 years, I have been able to pay off my graduate student loans, pay off my credit cards and am finally able to start saving for my retirement. Though I would now be able to pay rent if I choose, I would be sacrificing the savings I will need for a time when I can no longer work or for when any number of my classes may be taken away from me.

In addition, I payed out of my own pocket for the equipment necessary to transition from in-person to online in the beginning of covid. Also, each semester, quite a few of my students do not purchase many of the required materials necessary to participate in my class. For the last 14 years, I have spent on average about $300 every semester on materials for my students. I teach drawing. Over the years I have purchased in accumulation 30 sets of the types of items that can be reused (x-acto knives, 18 inch metal rulers, yard sticks, scissors, artsponges, brushes, crow quill pens and nibs, etc….) so that I can significantly reduce the cost of materials for my students. How else can I keep getting these classes, if my students are able to stay in the class due to not being able to participate because of lack of materials (rhetorical)? So I made the choice to invest in this way for them and for me to have a successful class.

Also, over the years, I have gone from 1 class, to two, up to four and then suddenly back down to 1. Currently, I have been teaching 3 to 4.5 classes. The .5 is because of co-teaching due to the policy of not hiring adjuncts over a set load and so I am fortunate enough to get half a class on occasion from the same community college. However, I never know what classes I will be getting until close to the end of the current semester and so I can’t plan or budget more than three months into the future. I certainly can’t commit to paying rent if I legitimately never know if I will suddenly not be able to afford to pay it or if I have to spend my very hard earned (over a long period of time) savings that I will need when I am older and no longer working.

Each of us has a story and my story happens to include an SUV that I call home for the last 9 years and three months.

LikeLike